| The fall of the Berlin Wall, which occurred in 1989, is one of the most important moments of the 20th century. It also happened by accident, because of a faulty decision. Guenter Schabowski, a spokesman for the East German Politburo, was hosting a press conference about the possibilities of East Germany allowing travel through the Wall. Here’s the thing: Right before the press conference, Shabowski received a memo from Politburo feeding him talking points, but he didn’t read the entire statement. After nearly an hour of speaking, Schabowski became confused about what was actual policy and he overestimated the contents of that pre-conference memo. He mentioned opening their fortified border and travel possible for every citizen, which got the attention of the room. When a reporter asked when these earth-shattering changes would take effect, another reporter followed up and shouted “Immediately?!” Schabowski paused for a moment, made a decision, and answered with a distracted “Immediately! Right away!” This change wasn’t in the memo, but word quickly got out, and the rest is history. |

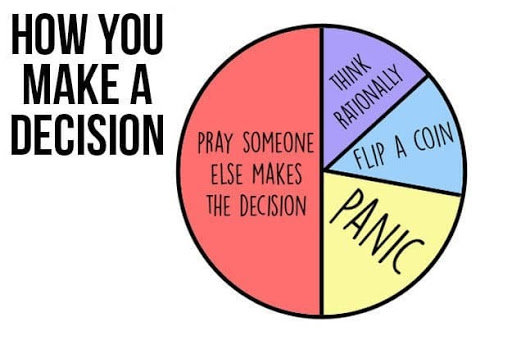

| I used to think that the most important part of my job was making the tough decisions. And I also thought I would be pretty good at that. I’m decisive, confident, fair, and impartial. Any decision is better than no decision, and I would be the person that would make those decisions. I guess a part of me still believes that, but I’ve also learned that reality is more complicated. When it comes to making decisions most people think they’re good at it. How hard can it be? You simply pick a side, take a position, or flip a coin. It’s red or blue, square or round, and that’s that. |

| When you’re a manager, entrepreneur, founder, parent, or really in any position that involves decision-making, the process goes more like this: nobody tells you in advance that a decision needs to be made, so the first challenge is recognizing the situations where a decision is needed. When presented with a simple binary choice, almost everyone can make a decision fairly quickly. Yet, there are rarely just two options, but 30, and each time you are close to a decision you’ll realize that your decision affects all the other choices. Nothing exists in a vacuum, and everything is connected. |

| The data is always incomplete, the outcome’s never sure, the risks are never detailed, and the upside rarely has defined edges. You should’ve decided yesterday, but you didn’t even know about it until today, and everything might be different tomorrow. You don’t want to be a dictator, so you need to ask people for advice, except that you don’t want to turn it into a committee meeting with ten different opinions. So ask a few, but not too many, but at least more than one and less than six. Every person you ask for advice will have a great story and valid reasons why it has to be X and not Y, and they’re all right. |

| You need to act fast, decide now, but do think about it, and not rush things. You trust your gut, but you also have to listen to your brain, and not ignore your experience, except that you can’t base your decision on results from the past. The painter Edgar Degas once said that painting is easy when you don’t know how to do it, but very difficult when you do. I now realize that the same goes for making decisions. The decision itself isn’t hard. The knowing when and based on what is what’s hard. |

Korean

Korean  German

German